Empathy, Environment, Effort

“The most unsociable empath”

For those that know me well, that descriptor is usually a fairly apt one. While I have no issues with fleeting social encounters, the increased intimacy of interacting with my friends is fairly laborious for me. A single outing or conversation is enough to overload my social battery for weeks, forcing a retreat to the comforts of the outdoors or my home, wherever “home” happens to be.

Currently, home is 69 degrees north, 350km above the Arctic Circle in the stunning city of Tromsø, Norway. It’s -16c, the winds are howling and I’ve retreated from the nearby park to the Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum, or Northern Norwegian Art Museum, where an incredible exhibit is on display.

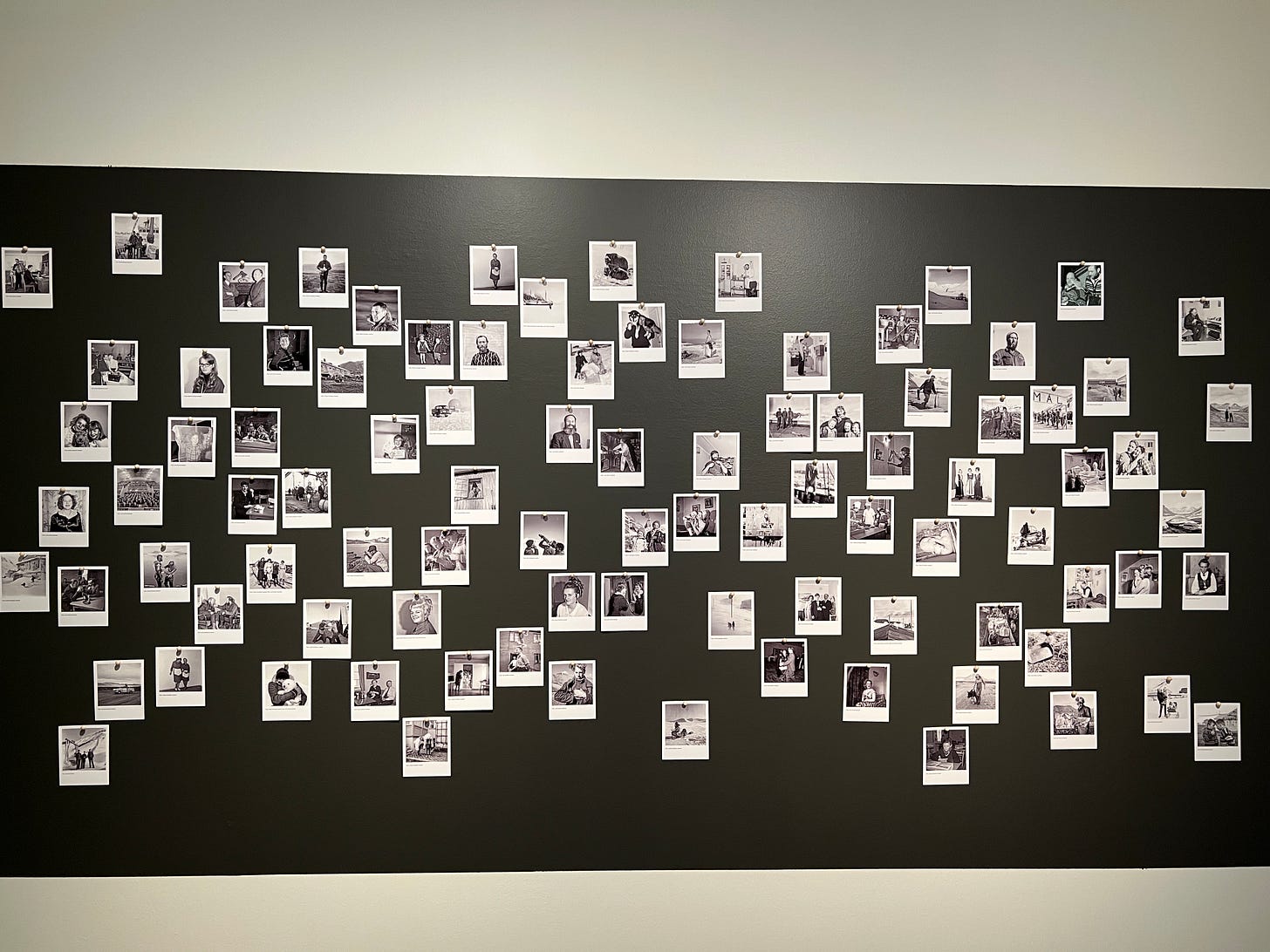

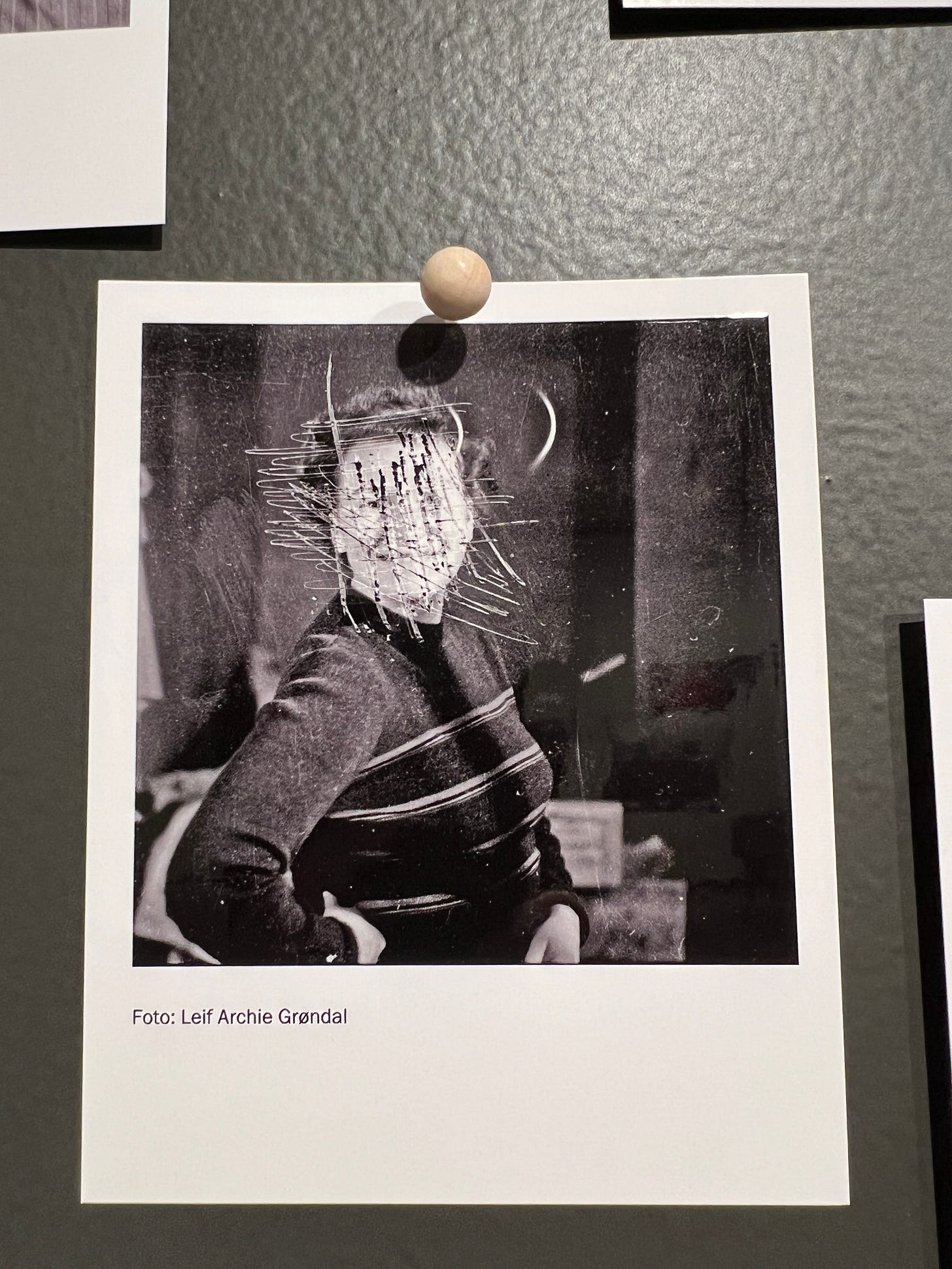

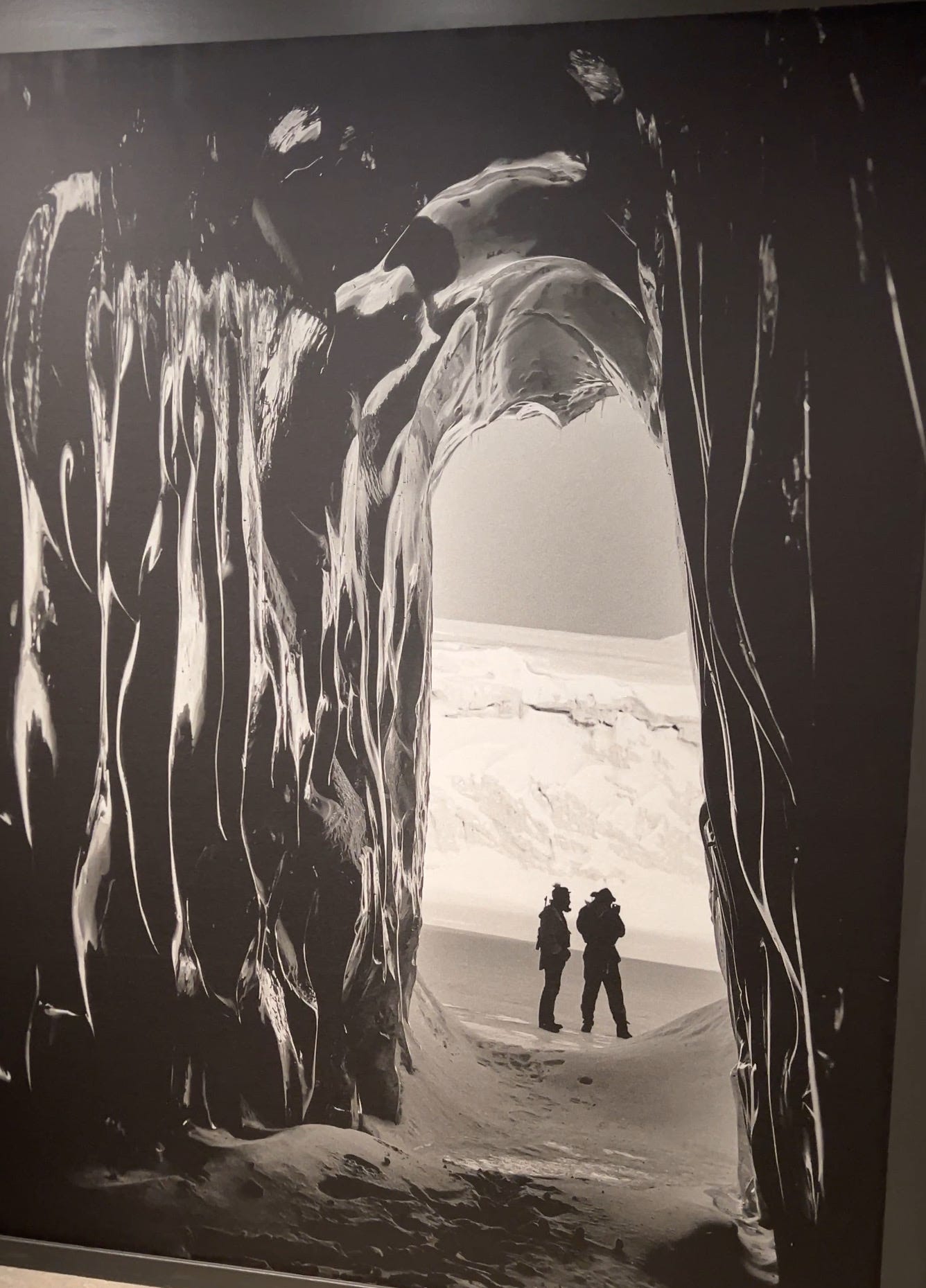

It’s titled “Layers of Time - Everyday Life in Svalbard.” It’s a collection of art, mostly photography, created across three generations of the Grøndal family. It features mostly images created by Herta and Leif Grøndal, their daughter Eva Grøndal, with an accompanying soundtrack made by Eva’s daughter, Aggie Grøndal.

While this museum trip wasn’t on my radar, I find many of the best things in life occur when room is left for spontaneity. In the environments and situations I often find myself in, no amount of planning or weather radars can account for the actual conditions you’ll experience on site. I dragged myself out of bed at 4am, walked for an hour to the pier and boarded a boat to embark on a voyage through the fjords searching for humpbacks, orcas, and whatever other critters come my way.

I struggled to keep my eyes open while on top deck, my favourite part of any ship. As the engines started, stopped, started again, then stopped again - even my half woken brain could tell that I was soon to be back on land. The captain emerges from the bridge and says, “Man, I’m really sorry. We’re having some issues with the onboard systems and it’s just not safe for us to even think about setting sail right now. We’re going to have to try again another day.”

Except, I’m only here for a few more days and I’ve already got a full schedule ahead of me. There isn’t going to be “another day,” barring any further interruptions. I look at the captain and the crew; they realise my situation and seem even more upset about it than I am. I laugh, tell them it’s what it is and that I’ve not had breakfast anyways, inviting them to join me back on land. My offer is rejected, citing the more obvious, pressing issue of ship repair at hand.

After heeding their recommendations, I’m back on solid ground and eventually arrive at the Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum or Northern Norwegian Art Museum (I’ll be referring to it as “The Museum” for the remainder of this post).

Downtown Tromsø is a fairly touristy place. It’s tougher to find locals than it is to find foreigners; as indicated by the sheer number of souvenir shops in the area. I wasn’t expecting much, especially since the Troll museum I’d just emerged from was somewhat of a bust.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. What I’d stumbled upon was quite possibly one of the most powerful photography exhibits I’ve had the pleasure of experiencing. To set the scene, the Museum has begun dedicating a large portion of its exhibition area to female and non-binary artists, acknowledging that they’ve been historically and globally underrepresented.

Currently, all exhibits on display are made by women (with the exception of some images made by Leif Grøndal).

On the walls are images of the people of Svalbard, mostly coal miners. To be clear, Svalbard is one of the few places on earth where there are no indigenous populations of any kind. Not even eskimos, or the regional Sami people bothered to settle there. Members of nearby countries began to temporarily settle on Svalbard as early as the 1600’s, but industrial mining operations didn’t truly take place until the Norwegians and Russians built permanent mining infrastructure in the early 1900’s.

From 1952-1974, Herta Grøndal worked as a photographer on the archipelago. Despite the strict “boys club” nature and political restrictions of the various mining towns, Herta was granted access to both Norwegian and Russian settlements; an achievement on top of being one of the few women who were allowed to come to the archipelago, and one of even fewer women who enjoyed the freedom to roam within all areas of the various settlements. Herta continued visiting Svalbard as recently as 2008.

Herta was initially trained as a musician, not as a photographer. Much of her images are snapshots, interspersed with scenic panoramas. Despite this, she clearly knew her craft with the camera, and her work certainly has a distinct style to it no matter what she’s photographing.

We see images of coal miners contorted in the mines wielding drills and axes. We see tiny structures, dominated by the towering peaks and fjords across the archipelago. We see primitive shelters, snowmobiles, and the stark contrast of ash-covered miners against the omnipresent white snow.

As I sat listening to Aggie’s music, flipping through these “everyday” scenes, I’m teleported to the town of Longyearbyn. The sounds of drills running, frantic shower houses, and polar winds dominate the atmospheres of Aggie’s soundtrack.

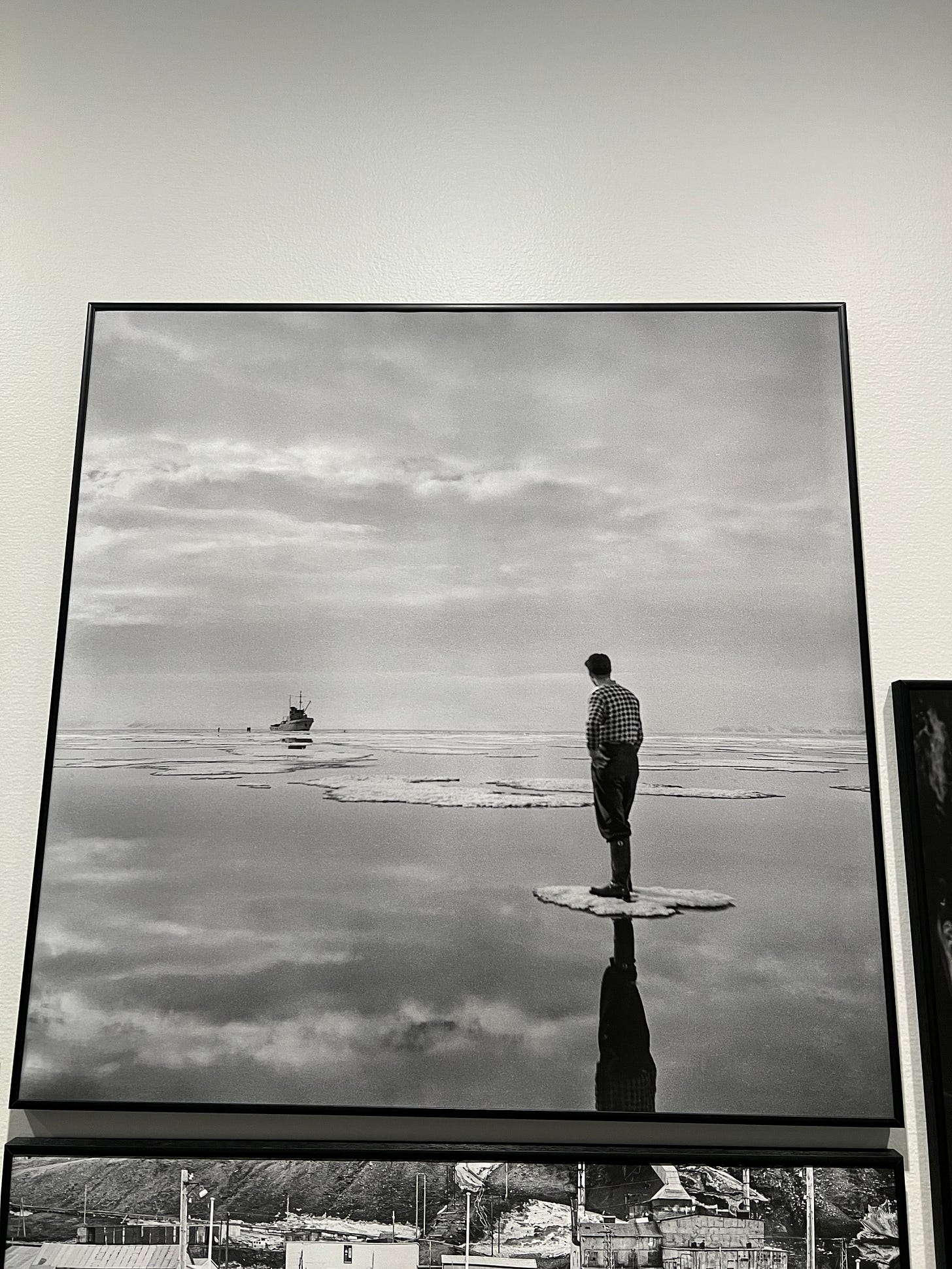

My Fjallraven jacket starts to feel like the fur coats the miners wore outside the caves. The LED headlamp in my pocket feels more intrusive, like the bulb based headlamps the miners used. I start picking up scents of coal from the freshly cleaned floors of the Museum. I feel the isolation of the miners, waiting on the permafrost runways for a resupply plane - one of the few indicators of the passage of time in the archipelago.

Moving onto the next half of the exhibit, Eva’s images are placed next to some of Herta’s. Eva followed Herta and Leif to Svalbard on several occasions, inspiring her series of “re photographs,” where she travels to the same locations depicted in Herta’s images and recreates them with their modern equivalents.

Herta’s images are mostly black and white, while Eva’s are in colour. The peaks, buildings, and equipment in the background are identical across both images, but the machinery and clothing worn by those in the foreground have been noticeably updated in Eva’s images.

I flipped page after page, reading the accompanying paper written by Elin Haugdal titled “Mediating Everyday Life In Svalbard: Herta Grøndal’s Photograohs, 1950s-70s.” It’s an incredible write up on Herta’s life, the lives of the early Svalbard miners, and the impact of Herta’s work. I soon found myself overwhelmed with emotion, having to stand aside and wipe tears from my eyes.

What an experience, what a story. For Aggie to listen to these recollections and memories from her mom and grandmother, for Eva to have accompanied Herta and then revisiting them in the future, for Herta to have been the pioneer of it all, for the miners, the wives, and children that found a life in one of the most remote areas on earth.

Inevitably, the conversation in my head turns back to me. I’m wondering if my work will ever have this kind of impact on someone else. Herta had to endure all sorts of social and political strife to work on her images, not to mention the danger and logistics of travel and outdoor exploration before our modern luxuries of hot water, rechargeable batteries, and synthetic down coats. I don’t mean to downplay the struggles I or others in my position face (an Asian male that has failed all of his parents expectations and chosen the path of an artist), but comparatively, I think I have it easy.

Which doesn’t really help the self-guilt I feel at not being able to work on my polar project today. Hours after the Museum visit, I’m back in the warmth of my host’s house and writing this in the detached room feeling like Emerson or Thoreau writing in their lakeside offices, though missing all of the finesse and lingual ability. It feels undeserved.

After all, everyday I’m not photographing despite being out in nature is, well, essentially just a vacation. And given how the first month of 2025 has been so far, it feels very wrong to be on vacation while my compatriots, the wildlife, and ecosystems are struggling so terribly with the backwards changes made by the facists and oligarchs that have installed themselves in the US government.

My heart breaks, aches, and cries for the marginalised people, exploited lands, and soon to be homeless or even extinct wildlife populations in the US. I feel so powerless in the face of these times.

Will my work reach people like the Grøndal’s reached me? Will my work have the same impact on others like Herta’s family did to me? Will people be moved to the same extent as I’ve been? Enough for them to want to write about, discuss, share, appreciate, and act on it?

I can only keep working away and hope that the answer is yes.

On another note, it’s also Chinese New Year’s Eve today, as well as the birth week of me and my cat, Bongo. I really should be at home, relaxing and celebrating with my friends (many of whom also had/are having their birthdays this month) but instead, I’m here in Tromsø by myself. Not that I’m complaining, it’s just that not being there for my friends and my cat is adding a little to that self-guilt.

Oh well. The search for wildlife hopefully continues tomorrow, pending further interruptions. Anyways, thank you all for reading as always, and Happy Chinese New Year from 69 degrees north!

RESOURCES:

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-43841-7_4

https://www.nnkm.no/en/exhibitions/layers-time-everyday-life-svalbard

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Svalbard